Fighting against oversight.

Keeping in memory.

Giving voice to those who have been silenced, and listening to that silence.

letting it vibrate.

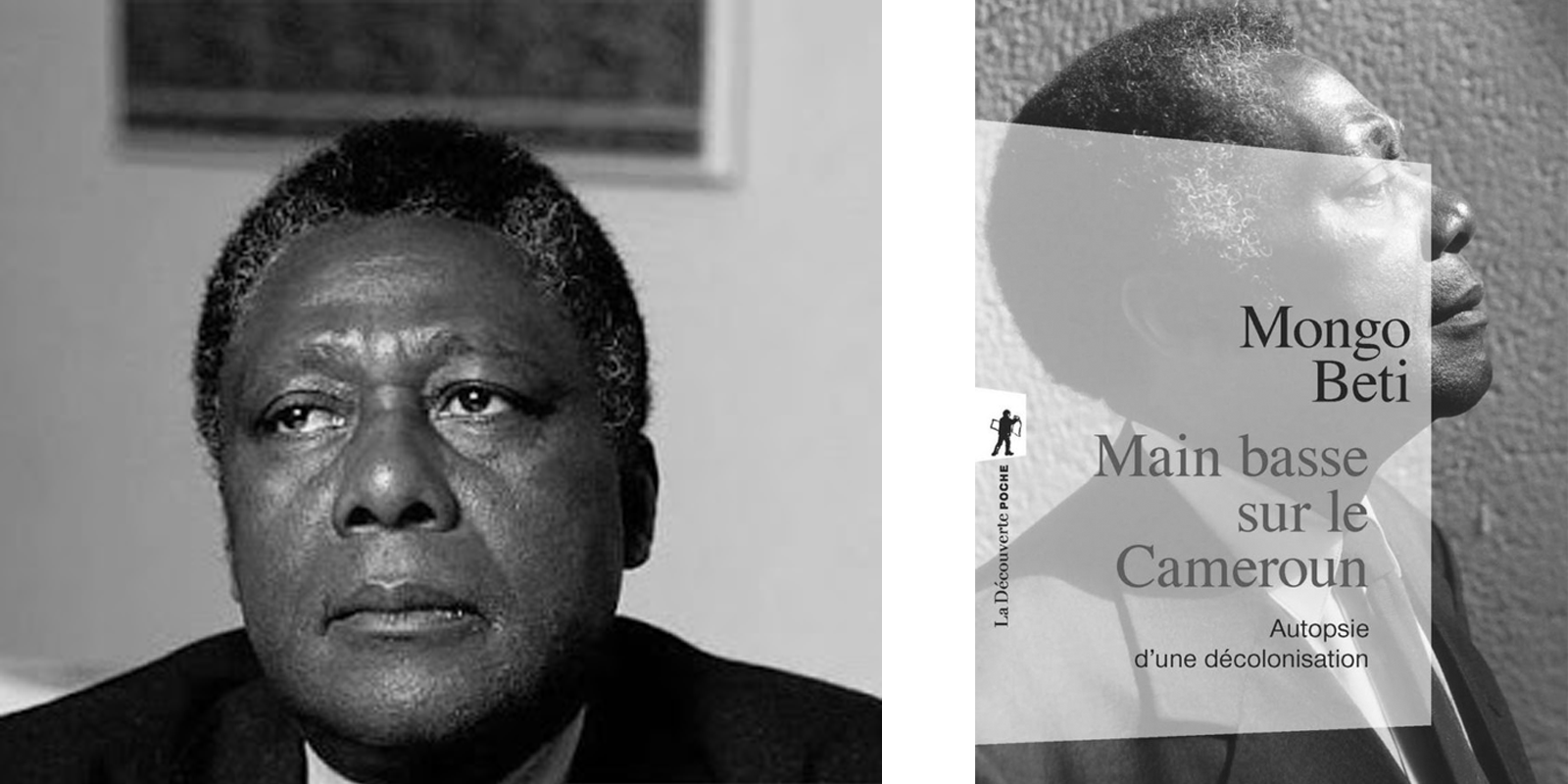

These are ideas that can be associated with the book « Main basse sur le Cameroun » published in 1972 by the Cameroonian journalist Mongo Beti about the war of independence and its repressive apparatus. The book was censored a few hours after its publication; the publisher was prosecuted and the author threatened. Has the objective been reached? Fifty years later, « Main basse sur le Cameroun » remains a major historical document. A source of questioning and inspiration that touched the young author Annick Kamgang, with whom we are talking today. Her creation, a graphic novel, this research in the depths of a collective as well as individual memory, is being carried out within the framework of a writing residency in partnership with the French Institute of Cameroon. A residency that has existed since 2013 with the aim of promoting literary creations of all genres from the Francophonie. At the Gacha Foundation we welcome them at the Villa Boutanga, our guest house. The writers have an ideal setting before them, at the top of the Bamilékés mountains in the west of the country. This is the first time we welcome a comic book creator. One morning, right after breakfast – made with organic and local avocados – we settle down on the terrace of the Villa for a lively, passionate and exciting exchange, which contrasts with the calm that emanates from the breathtaking view of the mountains surrounding us, that listen to us, in silence.

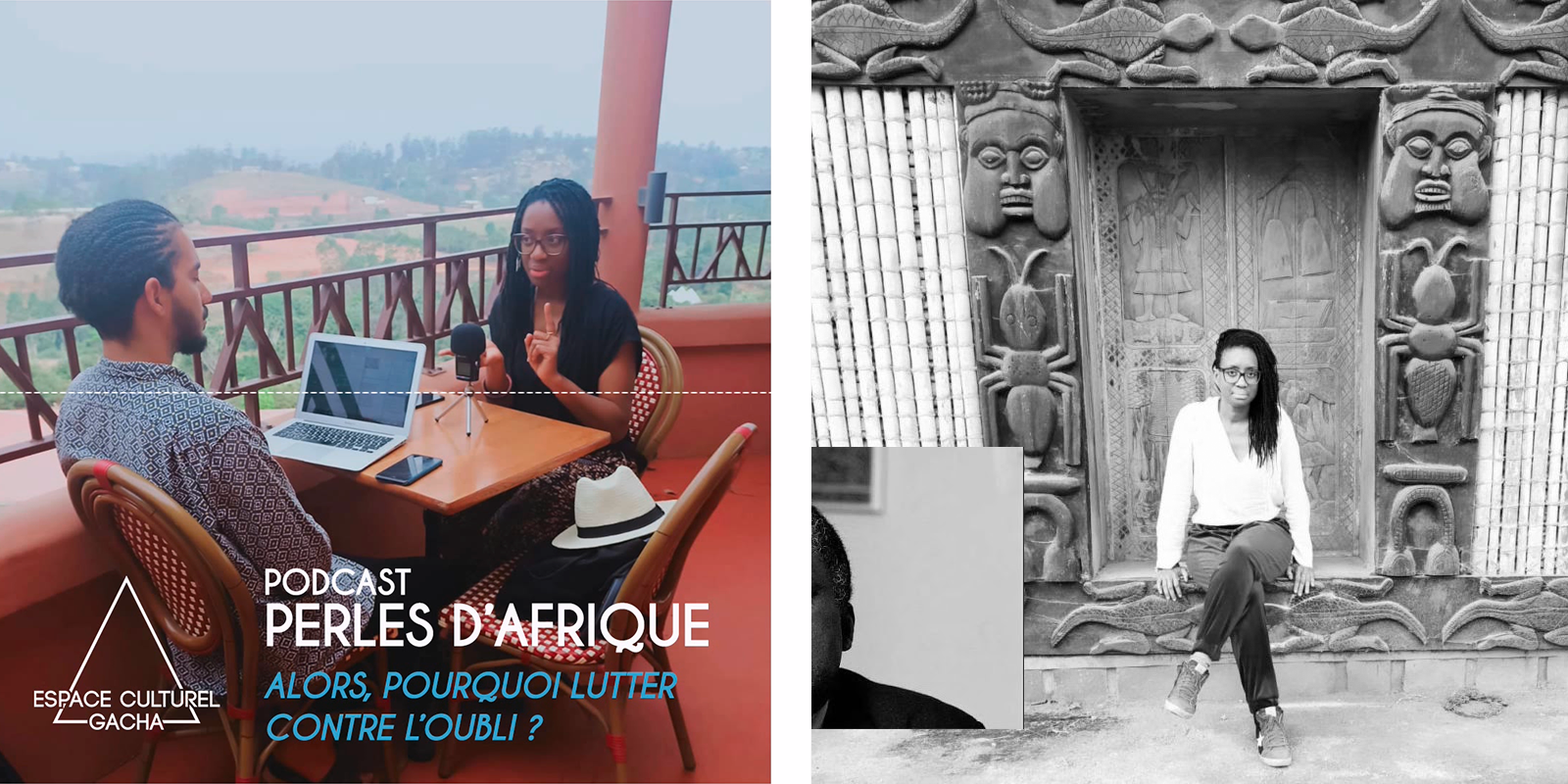

Podcast: Pearls of Africa – Annick Kamgang – So why fight against oversight?

Directed by: Espace Culturel Gacha

Left: Annick Kamgang’s interview with Danilo Lovisi, on the terrace of the Villa Boutanga, guest house of the Jean-Félicien Gacha Foundation in Bangoulap. Right: Annick Kamgangat the chieftaincy of Bamendjou. Cameroon, March 2020

DL: Annick, first of all, on behalf of the Jean-Félicien Gacha Foundation and the EspaceCulturel Gacha in Paris, I welcome you. To Bangoulap, to the Villa Boutanga, to the Foundation. We are delighted to welcome you here as part of this creative residency, in partnership with the French Institute of Cameroon. Could you please introduce yourself?

AK: Then my name is Annick Kamgang, I am a Franco-Cameroonian comic book author and cartoonist. More specifically Guadeloupean-Cameroonian. I was doing press cartoons in 2015 and I was particularly interested in current events rather African, and in a logical continuation I am now devoted to comics that allows me to explore certain topics related to Africa that are close to my heart.

DL: Since when have you been using comic books as a medium of creation, and why did you choose this medium to address these historically and humanly complex issues?

AK: So I am a young author in the profession, but not too young. In comics because my first work was published in spring 2018 at the editions la boîte à bulles in partnership with Amnesty International. It’s a comic book that tells the story of Lucha, a group of young Congolese activists mobilized on human rights issues, such as the presidential election in the Democratic Republic of Congo that was supposed to be held in 2016 and which finally took place in 2018.

They are campaigning for access to quality and free education for all. This is my first comic book work, it is in line with what is called comic journalism and reportage comics, which is a comic book that tells the news, that tells the world, which is a genre that perhaps allows people who are not interested in comics to understand certain subjects related to current events, to social issues. To grasp and understand these subjects through comics, that’s the trend I’m part of.

DL: Could you tell us about the writing project that is taking you to Cameroon today, its starting point, the resource people for carrying out this research?

AK: The starting point of this project Main basse sur le Cameroun is the title of the project which will perhaps evolve. The starting point is a meeting with one of the authors of the book Kamerun, a hidden war at the origins of Françafrique. This is a book that was published in 2011 that tells the story of the war that the French authorities waged against Cameroonian nationalists from the 1950s to the 1970s.

It had been in my dresser, in my library for the last 1 or 2 years. I didn’t have the courage to read it and then I said to myself « good! This is my chance, I’m reading this book » and in fact when I closed it I was extremely upset, extremely shocked to learn this story of which I knew bits and pieces before? I had heard about massacres, I had heard about genocides but I didn’t know that they were part of a more global war. So my father is Cameroonian, and he wrote his memoirs in 2012, and I had read his memoirs, and when I close the book on Cameroon I look back on his memoirs and in fact I read them with this new light on this war, and in fact what he writes makes sense, and now I say to myself: Annick, you’re in a subject where you can’t help but go ahead.

Mongo Beti – Source: Monwaih

DL: This graphic novel will take place at her time, who will be the characters?

We will talk about this subject through two characters: the first character Mongo Beti, a Cameroonian writer who in 1970 learns that one of the last great leaders of the Union of the Populations of Cameroon (UPC) which is the national liberation movement that fought for independence, is going to be executed and in fact he is indignant at the way the press in France treats the subject.

He believes that the subject is not being treated at its true value but that, moreover, the information that is said in the media is relatively false. So he is indignant, he takes up his pen and after a year he publishes a book called Main basse sur le Cameroun where he recounts the war, the repression of the UPC movement and at the end his book is censored and seized by the authorities. It is only a few years later that the book is published in France. The story it would be Mongo Beti who takes up the subject, takes up his pen, talks about the war in Cameroon. He would have flashbacks on the war through the character of Ernest Ouandié – one of the last nationalist leaders. He would have flashbacks on the war through this character. That is the initial idea, and because I am in residence for two months, I will take advantage of this presence in Western Cameroon and later in Yaoundé and Douala to enrich my account with the testimonies of people who were eyewitnesses to what happened. There are still veterans, people who are still living. It is important to know that the struggle that was led by the nationalists was led by people who were in the prime of life between the ages of 15 and 25. If I do not have access to veterans, there are also their descendants, because there was a transmission, which remained somewhat hidden, but which took place within the families, and I also rely on that. My work is a graphic novel, it’s the image, so I need a photo archive, that’s why during the Yaoundé stage between the 1st and the 15th of April I would like to go to the National Archives in Yaoundé. I know that there is a part dedicated to the photo archives to enrich my work even more, to give it a stronger solidity.

DL: It would be a form of fight against oversight? A device to keep and protect the memory?

Yes, so why fight against oversight? Because today this historical episode has been passed over in silence. I have learned that school textbooks today speak of the decolonization of Cameroon, but in a rather light-hearted way with regard to what happened. I think that today it is essential to work on this subject because it has been ignored, because that was the intention at the time of that war. The instructions were: we don’t want journalists in places where there are conflicts, we don’t want articles on what is happening, and we want total silence.

DL: How do you plan the creative process, what method will be used?

There are two things, I meet the witnesses, I rely on people who belong to a collective that militates so that this historical episode in Cameroon is not forgotten, it is thanks to them that I have access to these witnesses. There are people who belonged to the Union des Populations du Cameroun, people who did not belong to it because the people were also repressed. But I also have witnesses who were part of the repressive apparatus.

I couldn’t do a story about the Cameroon War without going through the Douala stage and the coastal region, why? Because the UPC was born in Douala in a neighbourhood called New Bell and also because one of the four regions, apart from the west which was one of the regions at the heart of the war, there is also a region called Bassam country, which is the maritime war. It is also one of the regions at the heart of the war and that is the coastline, and I cannot ignore it.

DL: The sharing of the evolution of the project is a moment planned within the framework of the creation residency. How do you envisage this action with the younger generations?

AK: First I would like to present my work and ask them at home to make me in two pages of comics the biography of one of the leaders of the UPC, Ruben Um Nyobe, Félix Moumie or Ernest Ouandié. I want to give them time to go home and read – or not. I don’t know what they have at their disposal. I’m aware that I’m in a high school in Bangoulap in the West, I don’t know what the high school library has. At the beginning, the idea would be either to tell them: I would like to do two pages of the life of one of the leaders of the UPC or, after they’ve read up on the subject, we could do another one or two hours together, that’s why I’d like us to do a workshop. in two steps. Another lead would be to ask them: what do you know about this story? Tell me what you know about this story, investigate your family to find out what they know and give me the results of your investigation in two comic pages. Maybe some people will say « I talked to my mother who told me that my grandmother/grandfather did this or that ». You give it back to me in two pages, or if nobody knows anything, you give it back to me in two pages.

DL: Is this work part of a decolonial movement?

AK: All that I can say to you it is that I am Franco-Cameroonian and thus of Guadeloupeanmother and I know the history of slavery. I know that I am descended from slaves, I know this history and I didn’t know it, or I had bits of information on what had happened in Cameroon. I just wanted to redress the balance, it seemed indispensable to me because, well, I’m going to say some rather naive things, but it’s true. You know where you’re going when you know where you’ve come from. That’s where I’m pushing open doors, that’sobvious, that’s my answer to these questions.

An interview conducted by Danilo Lovisi, as part of the ‘Pearls of Africa’ podcasts offered by the Espace Culturel Gacha.