© Staatliche, Museen zu Berlin / David von Becker

If today traditional sculptures from Africa reach sums up to Mount Cameroon in the auction houses, this is the result of a long Journey through a road full of obstacles to the change of certain preconceptions and stereotypes towards African cultures.

Beyond Compare : Art from Africa in the Bode Museum, Ausstellungsansicht, © Staatliche, Museen zu Berlin / David von Becker

The exhibition Beyond Compare (Bode Museum until June 2019 in Berlin) makes an important contribution to the dilution of a hierarchical vision of art that persiste in our day. The approach is both simple and daring: to present, side by side, exceptional pieces from Africa with Western works, Christianity, Greco-Roman mythology.

A bronze head of a king of the ancient Kingdom of Benin dating from the 17th Century faces a Roman marble from the 4 th representing an emperor. A Senegalese maternity dialogue with a pietà. Share the same room a Congolese magic figure of an animist religion and a sculpture of Saint Sebastian.

Beyond Compare : Art from Africa in the Bode Museum, Ausstellungsansicht, © Staatliche, Museen zu Berlin / David von Becker

The exhibition not only offers an aesthetic comparison, but builds bridges between different cultures. It shows that over the centuries societies in Africa and Europe have produced works that share common themes: the mytholgical representation of primordial beings, the effigy of sovereigns, the need for protection, maternity, the relationship with death, among others.

In order to give you glimpse of what you will find at the Bode Museum until June 2019, we share with you a few heart keynotes present in the exhibition and weaving an inter cultural loincloth synthesizing these reflections and questions.

Fundamental figuress :

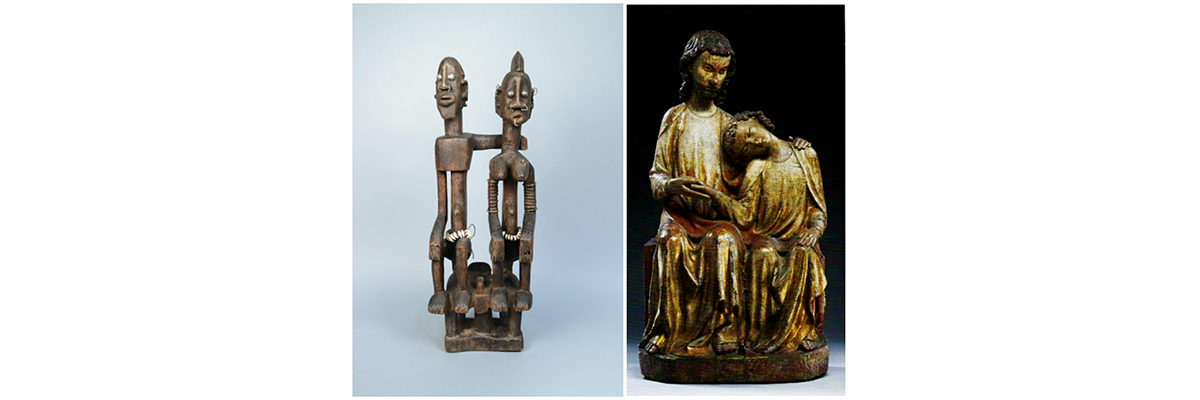

Pair of ancestors, Dogon, Mali / Burkina Faso, 19 th Century, Wood, cowry shells, metal, glass beads-acquired in 1909 by Leo Frobenius / Christ and Saint John, Lake Constance Region, 1310, polychrome oak – acquired in 1920 in Sigmaringen

Dogon myths (Mali or Burkina Faso) tha explain the origin of humanity, tell that the god Amma created androgynous beings at the beginning. This original, gender-neutral couple taught the Dogons essential life skills : working with the land, weaving cotton and the art of ironwork.

Surprising -or not- the philosopher of ancient Greece Plato, tell in his Banquet the myth of the Origin of love. Initially, human beings had a double body. Two beings in the same body, without any gender differentiation. We had three different sexes: male, female and androgynes. One day, following a revolt against the gods, Zeus, fuirons, decided to split them in two. Thus, these beings are forced to seek their half for all eternity.

Symbol of balance, the couple is often represented in a complementary way. This is the case of these two Dogon ancestors dating from the 19 th Century. Of an assertive and symmetrical front, the shapes show a a game of balance very pushed: the whole forms a square when the man’s arm touches the Woman’s shoulder. A square that is both stable and fluid; the cubic shape of the man’s torso is offset by the woman’s protruding breasts. If this first seems to be superior to his partner, the attentive observer will notice that the feminine hairstyle- sign of belonging to a higher class in Society – exceeds a man’s height.

Exposed side by side, another duo brings us a complementary dimension of the union between two beings, a mystic union; the ultimate union between man and the gods. It is a sculpture representing Christ and Saint John. Date 1310 it illustrates the Bible passage where Jesus announces that he will be the victim of a betrayal by one of his disciples. In a soft tone and leaning against Christ’s chest, John asks for the identity of the traitor. In a pursuit towards the essential, the sculpture dialogues aesthecally with the Dogon couple by removing all surrounding details.

The characters are part of in a harmonious interplay of vertical and diagonal lines. This slow dance of form evokes a relation of tenderness between the two figures : the childish face of John, the lightness of the two hands placed one on top of the other, the left arm of Jesus touching the shoulder of his disciple, the one with eyes closed. A whole that passes between stability and movement, physical and spiritual presence.

Need for protection

The search for protection by humans can take many forms. For centuries it was the role of the church to offer a heaven in troubled times. Today we expect governments and institutions to protect our physical and social well-being. We also call-privately and not collectively as religious-private insurance companies. Everything must be safe in the event of unforeseen circumstances; in case we find ourselves without knowing where to go, lost. Need for protection and guidance live side by side.

These fondamental questions have been embodied in works of art in the West and elsewhere.

Mangaaka – magical figure nkisi nkondi, République Democratic Republic of Congo, 19 th Century, wood, iron, porcelain – acquired in 1904 by Robert Visser / Virgin of Mercy, Michel Erhart, Germany, 1480, polychrome lime tree – acquired in 1850 for the Kunstammer

Christian relics-mortal remains or objects that belonged to the holy figures-were considered to have great protective power, and provide a link between the early world and beyond. In Central Africa, relics and ancestors play a similar role, protecting against threats from the physical world but also from evil spirits.

Among the Fang (Cameroon, Gabon) the relics are associated with medicine, as if the ancestors were also a source of life. In Cameroon, people often say: « The dead are not dead ».

We notice that the Saint of the 15 th century -on the last plane of the image- has very open, very white eyes, like the Congolese Nkisi figures. Both figures provide both spiritual and physical protection, with a view that sees everything. Generally, contact with these objects was limited to initiated persons or clergy.

In both cases these figures were only visible to a limited number of people, and shown on specific occasions, rituals and ceremonies.

Representation of sovereigns

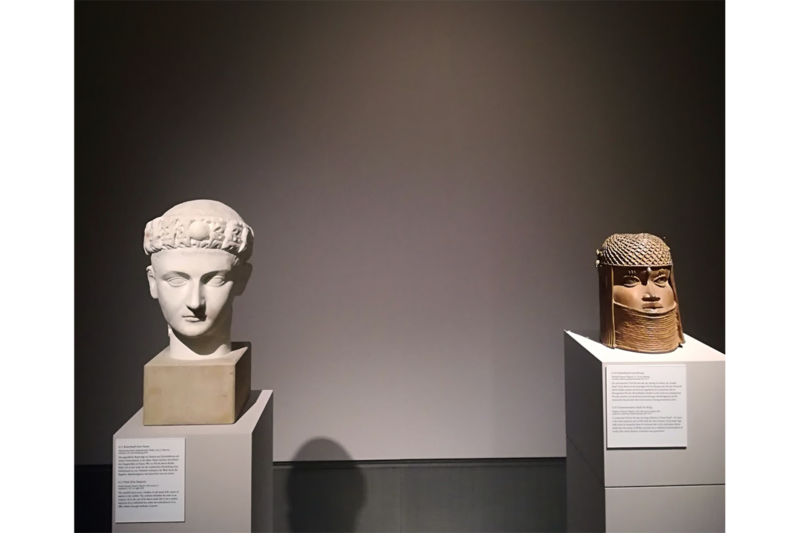

One of the most stripping works in the exhibition is a bronze head depicting a king of the Kingdom of Benin (currently Nigeria). Dating back to the 17 th Century, it impresses with its aesthetic strength due to the fine features, the composition of the accessories, and the technical rendering that would not question the expertise in ironwork art.

This during the 16 th century. Furthermore in Africa.

Head of Saint John the Baptist, Belgium, 1430, oak, acquired in 1898 by Consul Edouard Schmidt/ Head of an Oba, Kingdom of Benin-Nigeria- 16 th century, bronze, acquired in 1898

On the other hand, if we know some of these objects today, it is largely due to a punitive exhibition conducted by British troops in 1897. Excited and shocked by such a collection of bronzes, the soldiers looted the entire former Kingdom of Benin. Part of the booty was sold to cover military expenses, and the other part send to several European museums.

The minimalist scenography places this sovereign of the former Kingdom of Benin next to a marble representing en empereur of ancient Rome. The two sovereign heads play a rôle in preserving memory. Wearing attributes associated with a higher class-necklaces on the uppercut floor and scarification for the head of Benin, and an Oak diadem with a gemstone for Roman marble. The civilizational hierarchies are removed and the two pieces are presented as simply testimonies of kingdoms in the history of humanity.

Become an art

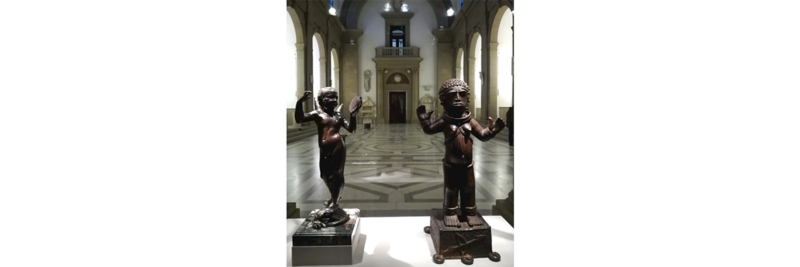

Statue of the goddess Irhevbu or Princesse Edeleyo, Kingdom of Bénin (Nigeria), 16 th century, copper, acquired in 1900 by William Adowing Webster / Cupid with a tambourine, Donatello, 15 th century, bronze, acquired in 1902 by the Durlacher Brothers

To enter the first room of Beyond Compare, the visiter has to push a very heavy iron door, as if a safe were being opened. These two pieces in copper and bronze welcome us. The history of their acquisition speaks volumes about the reception of African art at the beginning of the century because only one of them was acquired as a work of art, the other was only used as a witness to the know-how in ironwork for German ethnographic museums.

Their small format invites the viewer to approach and walk around the window. The poses are opposes. On the right, from the ancient Kingdom of Benin and date from the 16 th century, she representes the goddess Irhevbu or Princesse Edeleyo,with her hands up in the air, she would provoque an enemy. On the right, the body performs sensual turns, cupid dances and plays the tambourine. Focus is given to the movement of the arm before resonating on the tambourine, while the body weight changes from one leg to the other. Despites the splendid texture of Benin’s sculpture, the meticulous decorations, the scarifications and the strong and assertive frontality, it was not considered as an artistic work when it was acquired.

Today we understand these two sculptures as very important. The reception of these objects has changed and this is thanks to a long scientific, artistic and often militant work on the part of cultural institutions, art magazines, intellectuals and artists. By removing civilizational and artistic hierarchies, Beyond Compare is making an important contribution to this building. Beyond the comparison, the exhibition sets new standards: from now on, we will think twice about how, where and why to exhibit these works of art, and next to whom.

Danilo Lovisi, for Gacha Cultural Space

___

Why don’t we go to the museum soon ?

We offer cultural visits as part of our Manzeu cycle. Subscribe to our newsletter by clicking ici nd let’s stay in touch.

___

Photo credits :

Beyond Compare : Art from Africa in the Bode Museum, Ausstellungsansicht,

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / David von Becker

© Espace Culturel Gacha / Danilo Lovisi